Mobile phones are certainly ubiquitous—85% of Americans currently own a smartphone, and in 2020, 3.5 billion people owned a smartphone worldwide. With so many devices out there, it seems like mobile would be an excellent target for ransomware threat actors. However, we don’t hear a lot about devastating ransomware attacks targeting smartphone operating systems, like iOS or Android. Let’s explore why.

What Mobile Ransomware Exists?

Ransomware targeting Android often masquerades as a legitimate app, like the bevy of COVID-19-themed APKs that have emerged. While traditional ransomware encrypts the files on a user’s device, not all Android ransomware variants do so. Rather, this type of ransomware uses a few different types of techniques to deny a victim access to the device:

- Abuse of Android functionalities: AndroidOS.MalLocker.B, a sophisticated ransomware variant that emerged in late 2020, does not encrypt a victim’s files at all. Instead, it takes advantage of a high-priority “call” notification and overrides the onUserLeaveHint() callback to pop up the ransom note. Because this callback runs when the user presses the Home button or closes an app, this prevents the victim from dismissing the ransom note.

- Hijack User Permissions: Some Android malware, including ransomware and banking trojans, abuse the permission SYSTEM_ALERT_WINDOW, which allows the application to overlay a window on top of all other phone apps. While the files themselves are not encrypted, the ransom note screen will persistently overlay the screen, making the phone unusable.

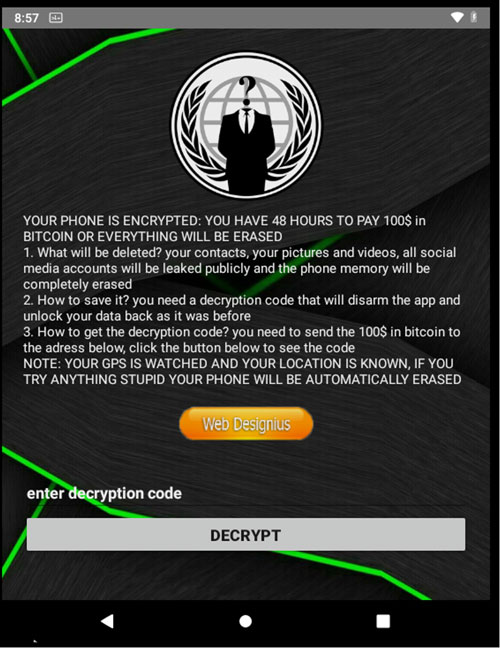

- Resetting the Device PIN: In addition to using AES encryption to encrypt the files in a device’s storage directory, DoubleLocker, which emerged in 2017, also changed the device’s PIN code to prevent access to the device. This technique was also used in 2015 by the aptly named Lockerpin ransomware, and a similar technique more recently in 2020 by CovidLock. A screenshot of the CovidLock ransom note can be seen in Figure 1.

- Extortion: LeakerLocker, an Android ransomware variant from 2017, locked the victim device’s screen, and collected information from it—including Chrome browser history, call history, pictures, and text messages—and threatened to expose it if a ransom was not paid. Researchers suspect this malicious application was a scam, as they were not able to identify code in the malicious application that would be able to send the collected data back to a server. Nevertheless, extortion remains a powerful technique used by ransomware to this day.

- Encrypting files: WannaLocker was an Android ransomware variant active in 2017 that was considered a “copycat” of the infamous WannaCry ransomware. WannaLocker targeted users in Chinese gaming forums, pretending to be a plugin for a game called “King of Glory”. Unlike the other Android ransomware variants mentioned, it actually uses AES encryption to encrypt the victim’s files, except those including “DCIM”, “download”, “miad”, ”android”, or “com.” in their path name.

Comparatively speaking, publicly known ransomware threats to iOS were substantially less prevalent. In early 2022, a researcher identified an exploit he called “doorLock” that can cause a denial-of-service for an iOS device by sending it into a reboot loop, essentially preventing the victim from using the device.

While the exploit itself is not ransomware, or known to be used in ransomware at this time, the researcher suggests it may offer a vector for future ransomware actors to target iOS devices.

Why Isn’t Mobile Ransomware More Popular?

Why is mobile ransomware relatively rare, given the prevalence of mobile platforms in our lives, both for personal use and business use?

First, users of Android and iOS devices primarily obtain applications from the Google Play Store or Apple App Store. Apple requires users to download applications from its app store, and applications have limited access to the device’s resources and data. This is known as sandboxing.

This, combined with the lack of publicly known exploits for iOS, and the fact that developers are locked in to Apple’s ecosystem for their implementation of application functionality, make it a substantially harder target for ransomware threat actors.

In addition to application sandboxing, many Android phones have Google Play Protect built in, which scans applications on the device for malware, while apps uploaded to the Google Play Store are scanned for malicious behavior as well.

Third-party app stores install APK files directly using the Android Package Manager, by using the “Unknown Sources” option offered by Android Devices. For those without access to Google services, third-party app stores are unlikely to implement malware-scanning protections, potentially leaving these users vulnerable to downloading fake apps.

Next, the sheer diversity of Android operating system types and the fragmentation of the market make it difficult for even legitimate developers to create applications that work on all devices.

While iOS is much more tightly controlled, Android, and operating systems built on it (like MIUI), is used by many device manufacturers and often customized by them. It should also be noted that getting “root” access, which would allow the threat actor administrator access to the device, is extremely challenging for mobile operating systems.

A Smaller Payoff

Finally, any ransomware tool development must be lucrative for the threat actor, which is far less likely in the case of locking a mobile device, as compared with locking all the Windows systems in an organization.

Both Apple and Android users have easy access to cheap, cloud-based backup tools—Apple iCloud and Google One—which makes it easy to wipe and restore their devices, in the event of a ransomware attack, with minimal loss of data.

In addition, most applications store data in the cloud, further minimizing the potential for data loss. As a result, not paying the ransom, outside of the possible threat of extortion, is much lower risk than it would be for a large organization unlikely to have such an easy route to recovery.

And finally, as we saw with the advent of big game hunting, locking individuals is just not as effective as locking large organizations who have a higher ability, and need, to pay the ransom.

The Possible Future of Mobile Ransomware

In the future, what could a successful mobile ransomware campaign look like? The most likely benefit a mobile device poses to ransomware threat actors would be as an initial access vector to other systems the device connects to, such as corporate resources.

As many individuals use their personal phones for work, this is certainly a possibility, though substantially more challenging than the same scenario would be if the device were a Windows laptop.

Additionally, exfiltrating the personal data stored on the mobile device and selling it or using it for other purposes is likely more lucrative for the threat actor. This is evident in the success of banking trojans, which largely target Android devices, and steal financial information from installed banking apps, often including SMS containing one-time passwords.

So, while mobile ransomware, and malware in general, will likely continue to exist, ransomware threats to Windows, Linux, and ESXi are substantially greater. However, it’s still important to use only legitimate app stores, ensure your mobile device and applications are updated, and be wary of phishing threats or those asking you to download suspicious applications.